Historic Hoi An

The small but historic town of Hoi An, located on the Thu Bon River 30km (19 miles) south of Danang holds far more appeal than its big northern neighbor. During the time of the Nguyen Lords and even under the first Nguyen Emperors, Hoi An – then known as Faifo – was an important port visited regularly by ships from Europe and all over the East. By the mid-19th century, however, the progressive silting up of the Thu Bon River and the development of Danang combined to make Hoi An into a backwater. The result is a delightful old town with many of its historical monuments preserved – a place where the visitor should linger and explore for several days.

Buy a ticket from one of the ticket offices around Hoi An. This gives you admission to all the old streets, one each of the three muse ums and assembly halls, and one of the four old houses. You also get access to a music concert or a handicraft workshop with this ticket. If you wish to see more places, buy a more expensive ticket. Most sights are open from 8am – 5pm and closed for lunch between noon and 2pm. Try to avoid visiting Hoi An at the height to the rainy season in October and November when waters spill over river banks and submerges many of the streets.

Perhaps the best-known historical monument in town is the Japanese Covered Bridge (Cau Nhat Ban). Originally built in 1593 by the Japanese mercantile community residing in Hoi An, this roofed, red-painted wooden bridge crosses a narrow side channel of the Thu Bon River in the western part of town. Though repeatedly restored, it retains its distinctly Japanese feel. A small temple, Chua Cau, is built into one side of the bridge.

Hoi An is famous for its traditional houses, most of which are found along Tran Phu, Nguyen Tai Hoc and Bach Dang streets, in the vicinity of the waterfront. Although generally still inhabited, these old mercantile homes are open to visitors.

Architectural Gems of Hoi An

The best-known is Tan Ky House, at 101 Nguyen Thai Hoc Street, a fine example of an 18th- century Sino- Viet shop house built around a tiny central courtyard. Look for the elegant ‘crab shell’ ceiling and the mother-of-pearl inlaid Chinese poetry hanging from columns supporting the roof.

The nearby Phung Hung House has been home to the same family for eight generations. Supported by no fewer than 80 hardwood columns, this building shows both Chinese influence (the gallery and shuttered windows) and Japanese influence (the delicate glass skylights).

Also worthy of a stop is Quan Thang House at 77 Tran Phu Street. Dating back to the 18th century, it features some beautiful well-preserved carvings on the inner walls. Look out also for the badge-like objects adorning the top of the door – this is said to guard the house from evil spirits.

The Chinese Presence

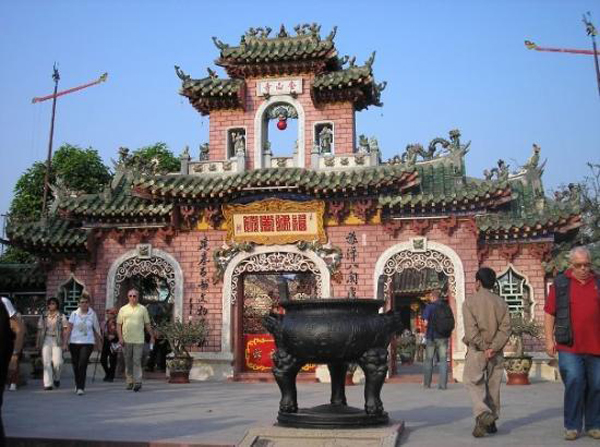

As throughout Southeast Asia, the Hoa (ethnic Chinese) merchants who dominated the commerce of Hoi An continued to identify themselves with their native province, and to this end built Chinese Assembly Halls to act as community centers and places of worship. Five distinct Overseas Chinese communities lived in Hoi An – Guangdong, Fujian, Hainan, Chaozhou (Teochiu) and Hakka – and all except the latter had their own Assembly Hall (the Hakka were able to participate in the Chinese All Community Assembly).

All five of these halls survive in Hoi An today, and are worthy of a visit, though if time is limited, the Fujian Assembly Hall at 46 Tran Phu Street is probably the most interesting. Founded in the mid-18th century, a new and elaborate triple-arched gateway was erected as recently as 1975. Inside is an altar devoted to Thien Hau the deity who serves as protector to fishermen and sailors. Also look out for the mural of the fathers of the original six Fujian families who sailed to Hoi An from China in the 18th century.

Hoi An also has several small but interesting temples which are worth visiting. These include Quan Cong Temple (Chua Quan Cong), located at 24 Tran Phu Street, which was established in 1653 and is dedicated to Quan Cong, a member of the Taoist pantheon who brings good luck and is the protective god of travelers. The Tran Family Chapel on Le Loi Street was established about two centuries ago as a shrine to the ancestors of the Tran family who moved from China to Vietnam around 1700. The building shows clear signs of Chinese influence, as does the Truong Family Chapel on a nearby side street running south of Phan Chu Trinh Street.

Temples and Tombs in Hoi An

The Chuc Thanh Pagoda, about 1km (1,5 mile) north of the town centre, is the oldest pagoda in Hoi An. Founded in 1454 by a Buddhist monk from China, the main sanctuary shelters a statue of the A Di Da Buddha, (Amitabha) flanked by two Thich Ca Mau Ni Buddhas (Sakyamuni). Phuoc Lam Pagoda, founded in the mid-17th century, is dedicated to An Thiem, a denizen of Hoi An who became a monk at the age of eight before becoming a soldier and rising to the rank of general. In later life, feeling guilty for all those he had killed, he returned to Hoi An and swept the local market for 20 years to atone for his sins.

Other points of interest include the Japanese Tombs (Ma Nhat), about 2km (1,25 miles) north of the town centre. The tombstone of the Japanese merchant Yajirobei, who died at Hoi An in 1647, faces northeast towards his homeland and is clearly inscribed with Japanese kanji characters. Nearby – it may be necessary to ask a local the exact whereabouts – is the tombstone of Japanese called Masai, who died at Hoi An in 1629.

My Son Holly Land

About 40km (25 miles) southwest of Hoi An, in the lee of Hon Quap or Cat’s Tooth Mountain, is My Son, site of the most significant Chair monuments in Vietnam. My Son was an important religious centre between the 4th and 13th centuries, serving as a spiritual counterpart to the nearby Amaravati capital Simhapura or Tra Kieu, little of which remains today.

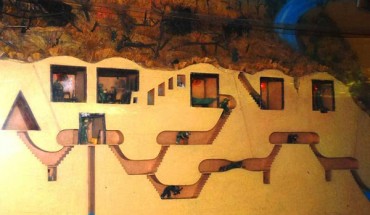

Traces of around 70 temples and related structures are still found at My Son, though only about 20 are in good condition. The monuments are divided into 10 groups, the most important of which are Groups B, C and D – Group A having been almost completely destroyed by US bombing during the Second Indochina War. The most striking of the monuments are the famed Cham Towers, tall sanctuaries made of brick bonded together in a fashion which still puzzles the experts, for no bonding material is visible. The best explanation offered to date – though it is still uncertain – is that the Cham master-builders used a form of resin to ‘glue’ the bricks together.

My Lai Massacre & My Lai village

Highway 1 south of Tam Ky passes through the provincial town of Quang Ngai. There’s not much to see here – but 14km (9 miles) northeast of town is the village of My Lai, site of the infamous massacre of Vietnamese peasants by US forces on 16 March 1968.

The village was supposedly a Viet Cong strong-hold, yet the residents turned out to be unarmed civilians. Several hundred people, including women and children, were shot to death that day. The American public didn’t find out about My Lai until the autumn of 1969, when a former soldier decided to write to government officials and force the truth out into the light.

Extra reading about Hoi An tours.