The Vietnamese people were able to enjoy independence for nine hundred years, challenged only by a brief Chinese occupation during the 15th century.

It would seem only natural that, following a long struggle for national identity, they would break with Chinese culture to further develop their Southeast Asian base. But the logic of history proved to be more dialectical.

From their position within the Chinese empire, the Vietnamese were apprenticed to study centralized power. In order to survive, they chose to imitate and copy their old enemies on both the material and the moral and spiritual levels.

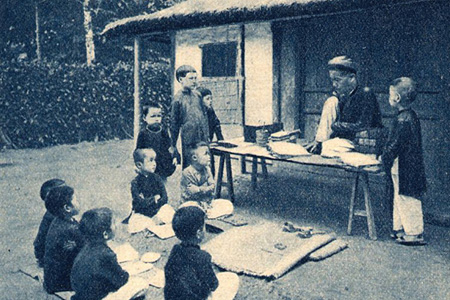

Diplomatic missions that were charged with presenting tribute to the Celestial court were also charged with bringing back precious books and recondite skills. Through this means a number of Chinese handicrafts were introduced to Vietnam by diplomat’s home from their missions. As a rule, these mandarins would then teach the skills they had appropriated to the people of their village. They are considered as "patron saints" and honored in the communal houses as tutelary gods who protect the village.

Confucianism, instead of being rejected, was reinforced. The kings and literati felt this ideology gave the nation more cohesion, and endowed it with a strong social framework, capable of resisting the attacks of foreigners. Historicist by nature, it fortified among the Vietnamese the cult of timeless myths.

Thus, the psychological disposition of the Vietnamese people towards China is ambiguous and even contradictory, marked by repulsion and attraction. The instinct for self-preservation necessitated the official relationship of a vassal paying tribute, but often such tribute was a facade. A sustained effort was required to confront the traditional Chinese politics: which were those of conquest or of maintenance of a weakened or divided Vietnam.

The essence of self-preservation for the Vietnamese lay in not allowing its cultural values to be altered. But at the same time, they were attracted by China's brilliant civilization, from which they sought to profit.

This dynamic of repulsion- attraction governed the political life of all the royal dynasties, up to the Western conquest during the second half of the 19th century. The dynasties legitimized their right to the crown by holding their own against the Imperial Court, by force of arms or by skillful diplomacy.

Ngo Quyen founder of the Ngo dynasty, put an end to Chinese domination in 938, and the process of the formation of a centralized monarchic state began. But the country passed through a period of instability due to the persistence of feudal divisions. Sung China took advantage of these to attempt a reconquest, but its expeditionary forces were beaten on land and water in 981.

It was only with the dynasties of the Ly and the Tran (11th-14th centuries) that the monarchy installed a truly stable power, and built a resplendent national culture in Southeast Asia.

Nonetheless, over the next four centuries it was necessary to repel several waves of Chinese invasion.

In the 11th century, confronting a new Sung Chinese offensive. General Ly Thuong Kiet composed a poem that may be considered the first proclamation of independence written in Vietnam:

"Over the mountains and rivers of the South reigns the Emperor of the South This has been decided forever by the Book of Heaven

How dare you, barbarians, invade our soil? Your hordes, without pity, will be annihilated!"

All of which did not keep the victorious general from negotiating peace with the defeated great power by proposing to cede five border districts, even though he regained them later by negotiation.

In the 13th century, the Mongols of Kubla Khan launched three large-scale attacks on Vietnam, and three times their armies were defeated.

The Ly-Tran period witnessed a remarkable cultural flowering; Buddhism played the dominant role, with Confucianism gradually gaining political influence. A national literature began, using borrowed Chinese ideograms while a national script based on Chinese characters was created.

Religious architecture and sculpture flourished, with a multiplication of pagodas and temples. The popular opera Cheo and the classical opera Tuong, as well as the water puppets, were established. Great public works projects - in particular, the dykes - were undertaken.

At the beginning of the 15th century, Vietnam suffered the cruelest oppression of its history, under the 20-year occupation by the Ming Empire of China (1407-1427). The administrators began a systematic policy of assimilation, forcing the population to adopt Chinese clothes, usages and customs. All vestiges of national culture were destroyed, including important literary works, and the best craftsmen and intellectuals were taken to China.

After putting up fierce resistance for 10 years, Le Loi was at last able to break the foreign yoke. The Le dynasty that he founded lasted until 1788. The new regime had a firm foundation thanks to the growth of private ownership of the land, which brought in its wake the rise of small landowners. The Confucianism that had become a true State doctrine, at the expense of Buddhism reinforced the absolute monarchy. But the crisis of feudal society caused a schism between the North and the South that lasted 200 years. The country, in its south-ward push, reached the Mekong delta.

At the end of the 18th century, the peasant insurrection of the Tay Son swept out the feudal lords of both the South and North. King Quong Trung, the famed leader of the uprising, crushed the Siamese troops and cut to pieces an army of 200,000 Chinese that had seized Thang Long (Hanoi).

The brief dynasty of Tay Son was succeeded by that of the Nguyen, which made quick to close the country to outsiders, except to China which served as their model for politics and philosophy.

The conservative Confucian elite that had contributed to forging a nation-state was equally the cause of the loss of that state. In 1883, the Court at Hue capitulated to the French.