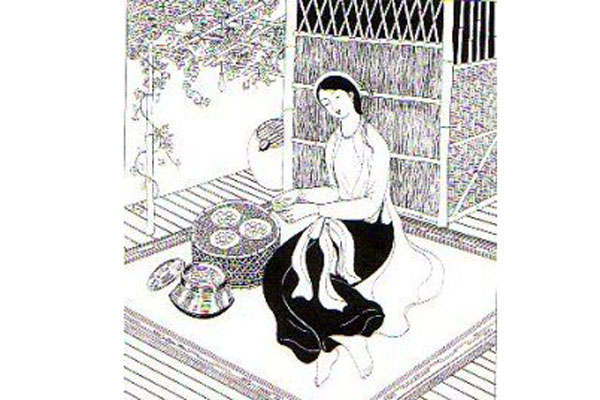

Ho Xuan Huong denies the male's superiority consecrated by Confucian ethics. She complains of the fate of unlucky women.

A lonely voice, unique in feudal literature, she rises with bitterness against concubinage.

To share a husband with another... what a life!

The one sleeps under the covers, well tucked in the other freezes.

By chance he comes across you in the dark, once or twice a month... nothing!

You hang on hoping to get your share, but the rice is poor and underdone.

You work like a drudge, save that you get no pay.

And had I known it would be like this

Willingly would I have stayed alone just as I was before,

In reading this poem, we are sure to think of this "ca dao" which is almost like a reply:

How unhappy to be a concubine

Transplanting

Tilling

And at night

No husband,

Quite alone,

Sleeping without a mat

In the biting cold.

“-Eh, you, the second one."

The first wife cries out,

"As early as daybreak

Boil the bran,

Peel potatoes

Chop duckweeds"

Oh, my dear parent,

Am I thus condemned?

Day after day

Because of your poverty?

Ho Xuan Huong also defends unmarried mothers while the society of her time condemned all extra-legal unions and qualified a pregnancy which had not been legitimized as a 'criminal pregnancy' (The unmarried mother, like the adulterous woman, was subjected to cruel punishments).

Her pleading is both ironical and sorrowful:

One moment of complaisance only and I’ve got into a mess!

Oh! My beloved one, do you feel my pains?

Heaven has no sooner given me the sign of destiny

Than a stroke comes to bar the willow trunk!

All your life, you’ll bear the burden of wrongdoing!

I accept to carry the fruit of our love!

I care little what people say about us

Cautious or not, I have my own wisdom making light of criticism.

The poet brings in an unequivocal verdict: the responsibility of the "wrongdoing", that is going to stain all the woman's life, devolves on the man.