No other work, except perhaps Nguyen Du's Kim Van Kieu has found more resonance in the Vietnamese soul than Chinh Phu Ngam (Lament of a Wife whose Husband has Gone to War).

Let us tell a few well-known anecdotes, for example, this true story about Uncle Ho.

It is told that, in the first war of Resistance, during the long marches through the forests of the north, Ho Chi Minh, in order to forget fatigue, solitude, and the length of the road, recited the verses of Chinh Phu Ngam and taught them to his liaison officer.

And here is an account given by one of my friends, an elderly woman

After being educated in a French school, she was going to enter the university soon after when she got married. Like all Vietnamese women of her epoch, she devoted all her time to housework.

When we asked her what was still left to her after her years of study, she answered: "Just a few verses of Chinh Phu Ngam which I sing to lull my baby to sleep".

How many mothers, in town or in the country, still sing some of the verses addressed to the far-off husband!

Such was the popularity of Chinh Phu Ngam that during the war, its first verses were made the words of a "national anthem' by the Saigon administration.

At the same time, teachers and critics in the northern marquis discussed whether it was advisable or not to remove Chinh Phu Ngam temporarily from the programmed of elementary and secondary education.

They were afraid that this work would have a paralyzing effect on young people at the very moment when the nation needed to galvanize minds and hearts to struggle against the French. But the beauty of this work prevailed and Chinh Phu Ngam was kept on the school curriculum.

One attributes this jewel of Vietnamese classical literature to the author Dang Tran Con who wrote it in classical Chinese and to its translator Doan Thi Diem, one of the greatest poets of her epoch, without whom this work would not have had such influence on the Vietnamese soul.

Dang Tran Con, native of Nhan Muc Village (now a suburb of Hanoi), lived from 1710 to 1745 under the Posterior Le Dynasty.

After being awarded his bachelor's degree at the triennial competition he became a mandarin - investigator for the censor's office; he was also a fine scholar whose literary works bear testimony to a vast erudition and a delicate talent.

Chinh Phu Ngam was probably written in 1741-1742, a troubled period when the Le Kings, in decline, still launched many expeditions against the insurgents.

Le Duy Mat's rebellion gave the signal for great popular uprisings which were fueled by the despair of the peasants crushed by the weight of extortion, war, and misery.

Doan Thi Diem (1705-1748) is native of Hien Pham village (now part of Van Giang District, Hai Hung Province).

A sister of the famous scholar Doan Doan Luan and a second-rank wife of Doctor of Literature Nguyen Kieu, she was herself very gifted. She was renowned for many poems and a collection of legends in Chinese Han. Yet the most famous of her works is the translation of Chinh Phu Ngam: in nom (demotic script for transcribing the Vietnamese language phonetically), probably done during the time her husband was detached on a mission to Peking.

This traditional thesis as to authorship has been called in question by Hoang Xuan Han and the groups of critics "Le Quy Don' and 'Van Su Dia", who attribute this translation to Phan Huy Ich, a well-known XIXth century poet. Yet, for lack of irrefutable proofs, Doan Thi Diem is still considered to be the translator; this nevertheless does not stop debates in the circles of literary criticism.

In support of the traditional thesis, we allow ourselves to say that rare is the poem that has translated with more emotion and truth the sensitivity and suffering of a woman torn from her beloved.

The subject of Chinh Phu Ngam is simple: the suffering of a woman whose husband is gone to war.

The sensitivity which runs through all the work is essentially feminine, made of regret, anxiety, and suffering, but also of hope.

The period in which Dang Tran Con and Doan Thi Diem lived was a troubled epoch, an epoch of war which pulled man out of their home.

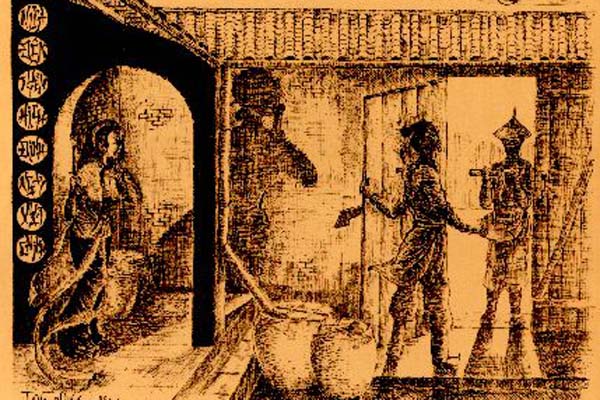

But the lament of this woman is not that of the wife of the soldier leaving home to join his frontier post, who accompanies her husband part of the way, weeping and crying.

The wife in Chinh Phu Ngam is not the one of the soldier in the 'ca dao" folk-song who,

A yellow bag in bandoleer,

A long gun slung over the shoulder,

Wearing a cone shaped hat.

In one hand a flint,

In the other a spear,