Like other religions, Catholicism views missionary work as a sacred and constant duty. Missionary work is actively encouraged in the Bible: "Therefore go and make disciples of all nations" (Matt. 28:19). With its missionary activities...

Like other religions, Catholicism views missionary work as a sacred and constant duty. Missionary work is actively encouraged in the Bible: "Therefore go and make disciples of all nations" (Matt. 28:19). With its missionary activities, Catholicism rose from being a local religion to the official religion of the Roman

Empire and later that of Europe. Due to the lack of knowledge of geography, however, it was wrongly assumed that the Catholic mission was completed following its prevalence in Europe in the fifteenth century.

The discovery of new lands offered the prospect of spreading Jesus Christ's name. This, however, created conflicts amongst developed countries, mainly Portugal and Spain, who used missionary work as a disguise for their colonial plans for these newly-discovered lands. When disputes over ownership of these new lands arose, the Vatican played the role of mediator.

By the beginning of the sixteenth century, in order to prevent disputes amongst leading European powers, the Vatican decided to fix boundaries of influence and missions. For example, in 1493 with the message "self-control," Pope Alexander VI divided the sphere of mission for these countries. Accordingly, Spain was awarded a sphere in the West (America), and Portugal's sphere of influence was in the East. An island in the Atlantic Ocean was used as the boundary between these two spheres.

However, Western capitalists did not develop equally, leading to the imbalance of power among them. From the middle of the seventeenth century to the eighteenth century, many new Western capitalists, including France, rose and became stronger and stronger while Portugal and Spain were in decline and no longer able to keep a firm grip on their colonies. This led to the Vatican re-dividing European countries' sphere of influence and missions. In light of France's economic ascension, Pope Clemens II gave priority to France by approving its missionary work in the Far East. His action contrasted to the message of "self- control" advocated by Pope Alexander VI in 1493.

The Church used missionary work to increase the spread of Christianity throughout the world. Meanwhile, European countries wanted to explore these new lands in order to support their capitalist economy they needed to seek new markets and new sources of raw materials for their own financial gain. As a result of these factors, an organic relationship between mission and colonization, which were compared to the cross and the cannon respectively, began.

That was the external context of the Western colonization and mission of the countries in the Far East, including Vietnam.

From the seventeenth to the eighteenth centuries, Vietnam was in a chaotic and complicated situation. The ruling class was in conflict due to the nation's separation, which started in 1645 and ended in 1692. The separation was caused by a power dispute. Specifically, at the end of the sixteenth century, the Le Dynasty began to fall into decadence, especially under the reign of Le Uy Muc (1505-1509) and Le Tuong Duc (1509-1516). When the Le Dynasty was replaced by the Mac Dynasty, the country was plunged into civil war. Nguyen Hoang (1525-1613), a mandarin under the Le Dynasty, moved to the South in 1558. He, together with descendants of the Le Dynasty, ruled over Quang Binh and a part of the Champa land which had become part of Dai Viet (Great Viet) since then. In the North, the Mac Dynasty was based in the mountainous area. As the Trinh Lords controlled the court, the Le Dynasty existed only in title. On the surface, the Nguyen Lords still submitted themselves to the rule of the Le Kings but not the Trinh Lords. Thus, the feudal group of Le-Trinh in the North (North of the Gianh river) and the Nguyen family in the South (South of the Gianh river) formed.

Afterwards, there was a civil war between Nguyen Anh and Tay Son brothers and the rehabilitation of the Nguyen family from the late eighteenth century to the early nineteenth century. As a result, the economy fell into decline, which led to widespread poverty and political instability. The situation in Vietnam at that time created favorable conditions for Catholic missionaries and Western capitalists to make their religious and economic conquest over Vietnam.

In the early decades of the sixteenth century, the first Western priests entered Vietnam to carry out missionary work. It is recorded in Kham dinh Viet su thong giam cuong muc (General History of Vietnam Compiled at the Emperor's Order) written in the Nguyen Dynasty that in March 1533 (the year of Nguyen Hoa under the reign of King Le Trang Ton), a merchant named Ignatius arrived via sea and evangelized in Ninh Cuong Village, Quan Anh Commune, Nam Chain District, and Tra Vu Village, Giao Thuy District. Many scholars who study Catholicism in Vietnam list the year 1533 as the beginning of Catholic missionary work in Vietnam. Later on, in 1550, a Catholic priest named Gaspar da Santa Cruz came to preach in Ha Tien Province. In 1558, some other priests including Luis de Fonseca and Gregoire de la Motte proselytized in the central region of Vietnam. In 1583, priests Diego Doropesa and Pedro Ortiz preached in the coastal area of Quang Ninh Province. Between 1533 and 1614, the majority of missionaries were from the Portuguese Order of Friars Minor and the Spanish Order of Preachers. They traveled to Vietnam on merchant ships. However, these early missionary works were unsuccessful due to the friars and preachers' unfamiliarity with the language system and terrain of Vietnam. In the seventeenth century, after being forbidden in Japan and China, Catholic priests came to Vietnam in increasing numbers.

From 1615 to 1665, Portuguese Jesuits based in Macau, China, entered Vietnam to carry out missionary work both in Dang Trong (South Vietnam) and Dang Ngoai (North Vietnam). On January 18, 1615, two priests named F. Buzomi and D. Carvalho arrived in Hoi An, South Vietnam. At first, their main objective was to preach to Vietnamese and Japanese merchants there. In 1617, other two priests, Phanxico de Pina and Phanxico Barreto, came to assist F. Buzomi as D. Carvalho had been killed in Japan. From 1615 to 1625, there were totally 21 assistants coming to South Vietnam to carry out Catholic missions, including 17 Catholic priests and 4 monks. Out of these numbers, 10 were from Portugal, 5 were from Italy, 5 were from Japan, and 1 was from France. For the first period of time, the missionary work achieved success as the people from Dang Trong were very open-minded and amiable. More importantly, King Nguyen Phuc Nguyen (in reign from 1613 to 1635) was determined to improve commercial relationships with Portugal and was therefore more tolerant of the missionaries than he would have been if the situation was different.

In 1615, the first church was built in Dang Trong. On Easter Day of the same year, 10 people were baptized, which raised the number of Catholics to 300. The number of Catholics continued to increase over the years. Followers were not only ordinary Vietnamese but also servants and relatives of the royal family, including Minh Duc, Lord Nguyen Hoang's concubine and Lord Nguyen Phuc Nguyen's mother's younger sister.

The Catholic missionary work in Dang Ngoai occurred ten years after that in Dang Trong. In 1626, Father Giuliano and a Japanese arrived in Dang Ngoai by a Portuguese merchant ship. However, the language barrier resulted in Giuliano leaving Dang Ngoai for Macau. Once in Macau, Guiliano suggested that the Catholic missionary work should be based there in order to avoid the Trinh Lords' suspicions.

After Pedro Marque, Gaspar d'Amaral, Antonio Barbosa and Alexandre de Rhodes came to preach in North Vietnam.

Like the Nguyen Lords, the Trinh Lords also initially had a liking for the Portuguese and wanted to develop commercial relationships with them despite their limited understanding of Catholicism. They even allowed Catholic assistants to preach in their palaces. Fluent in Vietnamese and clever in activities, the Jesuits attracted a great number of followers in spite of many difficulties. The creation of the Latin-based Vietnamese writing played an important role in the spreading of Catholicism. According to the statistics of the Catholic Church, after thirty- seven years of missionary work, there were totally 25 Catholic priests and 5 preachers in Dang Ngoai. And after fifty years of missionary work, there were 39 Catholic priests in Dang Trong. During this period, the Jesuitic missionaries were able to attract 100,000 followers, including 20,000 in Dang Ngoai and 80,000 in Dang Trong. In Nghe An in 1593, a total of 12 Catholic villages were established.

When Catholicism gained a solid footing in Vietnam, (he Jesuits found it necessary to have bishops who would be responsible for expanding the missionary work at a higher level. In 1645, after being permanently expelled from Dang Trong by the Nguyen Lords, Alexandre de Rhodes returned to Europe to report on the conditions in Vietnam and to encourage other missionaries to come to Vietnam. Although he was a Jesuit and had pledged his loyalty to the King of Portugal, he was French by birth so he still felt closely attached to France. Therefore, after realizing the depressed state of Portugal, he turned to his homeland and chose French priests to act as bishops in Vietnam. In 1659, Pope Alexander VII (1655-1667) appointed two Frenchmen, Francois Pallu and Lambert de la Motte, as bishops to take over the missionary work in Indochina. In the same year, the first two Catholic regions in Vietnam were established: one included Dang Trong and Cambodia; the other included Dang Ngoai, Laos and five provinces of South China. Bishop Lambert de la Motte was placed in charge of Dang Trong while Bishop Francois Pallu was given dominion over North Vietnam. In 1679, the region in Dang Ngoai was divided into two parts: West and East with the Red River and Lo River as the boundary. The West was in the control of Bishop Jacques de Bourges, and the East was under the authority of Bishop Francois Deylier.

During his stay in France, Alexandre de Rhodes persuaded the French King and aristocracy to petition the Pope to establish the Society of Foreign Missions of Paris (Mission Etrangeres de Paris - MEP). Finally, in 1664, the Society was officially established and commissioned by Pope Alexander VII to carry out missionary work in three regions. The first region included Dang Ngoai, Laos and South China; the second region was comprised of Dang Trong and Cambodia; the third regions consisted of several provinces in North China, North Korea and Mongolia.

The founding of the Society led to tensions between the Portuguese Jesuits and the Society. The Jesuits did not approve the dominion of the two French bishops; they even refused to receive their letters of introduction. Then the Jesuits took the French bishops to court but finally lost. In 1688, Pope Alexander VII solved the conflict by passing an ordinance that gave the Society the exclusive right to carry out missionary work with the support of the French government. Despite this action of the Pope, the Macau-based Jesuits continued to hinder the development of the Society. Eventually, in the late seventeenth century, Pope Clemens IX ordered the Jesuits to leave Indochina. After that, the missionary work throughout Indochina was completely under the dominion of the Society.

In comparison with the Jesuits, the two French bishops and other missionaries of the Society faced more difficulties when attempting to fulfill their missions in Vietnam since the second half of the seventeenth century. When the Jesuits first came to Vietnam, there was conflict between the Trinh Lords and the Nguyen Lords. Both camps encouraged the spread of Catholicism as it enabled them to develop relationships with Western powers, which would provide them with the weapons to fight against each other. However, by the time the missionaries of the Society arrived in Vietnam, the relationship between these two warring factions had improved. Therefore, the new missionaries had to disguise themselves as merchants with interesting gifts in order to enter Vietnam easily.

In 1662, after leaving France for Thailand, Bishop Francois Pallu sought the opportunity to preach in North Vietnam. However, he faced great difficulties in doing so. In 1664, the successor of Lord Trinh Trang (in reign from 1623 to 1652), Lord Trinh Tac (in reign from 1653 to 1682) passed a royal ordinance that forbade religions. Having heard of it, Bishop Francois Pallu sent a letter to comfort the followers. In 1674, he attempted to travel to Dang Ngoai by ship, but a hurricane forced his ship to anchor itself in the Philippines. After this failure, he returned to Europe.

In January 1672, Lambert de la Motte went to South Vietnam but was forced to return to Thailand due to the opposition of the Jesuits. In 1673, he dispatched the missionary Vachet and a Vietnamese who had been nominated as a catholic priest in Thailand to give presents to Lord Nguyen Phuc Tan (in reign from 1648 to 1687) before his visit to South Vietnam in the middle of 1675.

Despite having offered the Lord valuable gifts, Lambert de la Motte and other missionaries were not warmly welcome as before. After arriving in South Vietnam, he also took charge of Dang Ngoai in the place of Bishop Francois Pallu, who had failed to come. As a bishop, he was active in evangelizing the locals and promoting native priests. He was also the founder of the Holy Cross, the first order for nuns in Vietnam. In April 1676, he left Dang Trong and was later succeeded by Bishop Deydier.

In the early period of evangelization, apart from the Portuguese Jesuits and the Society of Foreign Missions of Paris, there were also missionaries from the Spanish Dominican order in Vietnam. Although their sphere of influence was confined to Dang Ngoai, especially to the East, they established 70 chapels and evangelized over 18,000 parishioners within the area under their control by the late seventeenth century as the result of their efforts.

As mentioned above, the missionary work in Vietnam was initially approved and even supported but later was forbidden by the Trinh and Nguyen Lords. However, the prohibition of Catholicism in Vietnam in the period of the Trinh and Nguyen Lords did not result from political issues but from ideological issues, especially rite-related ones. Moreover, Catholicism was not forbidden as strictly and systematically in this period as it was under the reign of the Nguyen court.

In 1628, Lord Trinh Trang promulgated a decree against missionaries as below: "I, the Lord of Dang Ngoai, am quite familiar with Western priests in my palace. But I do not know what they are intriguing at present and in the future. Hence, you, my people, are not allowed to contact them and follow their religion from now on. Those who do not obey this rule will be put to death. In 1663, King Le Huyen Tong (in reign from 1663 to 1671) passed a royal decree against the religion as followings: "Formerly, a Catholic priest called Hoa Lang entered our country along with Christianity to trick, entice and make Vietnamese people ignorant. He was previously expelled, but his followers are still propagandizing it in our country. Therefore, I once again have to announce my decision to ban Christianity in our country." In 1712, Lord Trinh Cuong issued this royal decree: "Although the Court has issued the prohibition against Christianity several times, many local officials and people are still being bribed to hide it. So it is still spreading more and more deeply among the population. Accordingly, I put a ban again on this religion in Vietnam. Those who denounce followers of Christianity will be rewarded with 100 francs. Secret followers of Christianity will be punished by having the words 'Hoa Lang's follower' carved onto their heads." In a royal ordinance issued in 1763, Lord Nguyen Phuc Khoat in Dang Trong asserted: "I am the Lord of Dang Trong. You, my people, are under my rule, not God's." As the result of this backlash against Christianity, 200 out of 300 churches in Dang Trong were destroyed in 1750.

It can be said that the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were the time of Spanish and Portuguese missionaries. But then, they gradually lost their influence in Vietnam while French priests became more and more powerful, especially after the establishment of the Society of Foreign Missions of Paris. In spite the Trinh and Nguyen Lords' prohibition against Catholicism, the number of followers in both regions still increased. This assertion is supported by the statistics of the Catholic Church which documents the number of Catholics in Dang Trong in 1644 as 100,000 and in Dang Ngoai in 1737 as 250,000.

The economic, political and social conditions in Vietnam in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries brought about important changes. The year 1771 was marked by the Tay Son movement led by brothers Nguyen Nhac, Nguyen Hue and Nguyen Lu. In 1777, the Tay Son army defeated the Nguyen Lords in Dang Trong. Lord Nguyen Phuc Thuan and all his loyal family, except Nguyen Anh, were killed. Nguyen Anh (1762- 1820) escaped and soon made preparations to challenge the Tay Son army. The Tay Son Dynasty was established in Dang Trong and eventually encompassed the whole country. The Tay Son Dynasty was famous for its glorious feats of arms against the army of the Qing Dynasty (China) and that of the Siam Dynasty (Thailand). However, the Tay Son Dynasty came to an end in 1802 following their defeat by Nguyen Anh.

The aforementioned historical situation created favorable conditions for the expansion of the Society of Foreign Missions of Paris. During this period, such priests as Lefebvre, Puginnier, Retord and Pigneau de Behaine took an active part in introducing Catholicism into Vietnam. However, when carrying out missionary work in Vietnam, some missionaries of the Society began to recruit a group of Catholic followers to assist French schemes for invading and dominating Vietnam. The summary record of the scientific seminar in Ho Chi Minh City in 1988, Mot so van de dao Thien Chua trong lich su dan toc Vietnam (Some Issues on Catholicism in Vietnamese History), published by the Vietnam Government Committee for Religious Affairs and Vietnam Academy of Social Sciences shows documentation regarding Catholic priests who were politically involved in the invasion of the French in Vietnam.

Here are some examples:

- In 1669, Bishop Francois Pallu in Dang Ngoai sent a letter to the Secretary of the French Navy demanding naval forces to invade the Red River Delta.

- Bishop Pigneau de Behaine (also called Ba Da Loc in Vietnamese), who meddled deeply in Vietnamese internal affairs, made plans to help Nguyen Anh rebuild his fortune and push Vietnam under the dominance of the French.

- Bishop Lefebvre frequently contacted French warships and helped them to invade Vietnam in the 1840s and 1850s. The loyalty of Lefebvre was highly honored by the French. A French historian said: "In the history of French conquests, we cannot forget Father Lefebvre whose patriotism made Annam become a colony of France."

- Bishop Pellerin initiated the campaign ipr the French armed-interference in Vietnam. It was Pellerin who suggested to French forces that they choose Da Nang as a target of attack

- Additionally, he was present on the ship of General Rigault de Genouilly on the open-fire invasion of Da Nang in 1858. Due to the difficulties encountered in Da Nang, he suggested Bac Ky as the next target of attack due to the large numbers of Catholic followers in this area, who were prepared to support the French in their military takeover of Vietnam.

- Bishop Puginier (Co Phuoc in Vietnamese) played an important role in the first French invasion of Bac Ky (Tonkin or North Vietnam) in 1873. He helped F. Garnier recruit about 2,0 Vietnamese soldiers, mainly Catholic followers. He had admitted that French troops would have no position in Vietnam without missionaries and parishioners. He died in 1892. In a telegram of condolence to the Bishop's office in Hanoi, the French Resident Superior wrote: "The Father's death is a great loss to the Catholic Church, especially to France and Bac Ky, where he made a great effort to help France take its possessions."

- The Nguyen Dynasty objected to Catholicism not only for political reasons but also for the strangeness of Catholic worship. Before Catholicism was introduced, the Vietnamese worshiped their ancestors and followed the three traditional religions, including Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism. The psychology, lifestyles, practices, customs and ethical standards of these religions were strikingly different from the values and beliefs of Catholicism.

Formerly, the Jesuits in general and Alexandre de Rhodes in particular sought a balance between converting the Vietnamese to Catholicism and allowing them to continue worshipping their ancestors and other cultural practices. However, the missionaries of the Society of Foreign Missions of Paris rigidly denied, prohibited and even desecrated the cultural values of the Vietnamese, which led to a culture clash. In the eyes of the Nguyen Dynasty at that time, the matter of religious rituals not only resulted in the Catholic community being separated from the remaining Vietnamese who practiced traditional religions but also contributed to the suspicion that Vietnam could be overcome by outsiders.

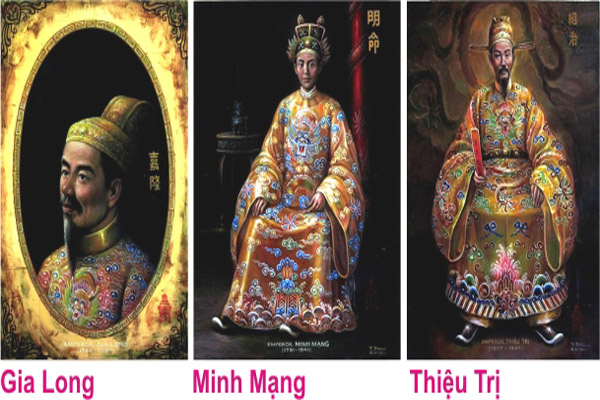

Besides the differences in ideology, religion and culture, it was the activities of French missionaries that mainly and directly ignited the suspicion of the Vietnamese kings and lords and caused them to prohibit Catholicism. During the reign of the first four kings of the Nguyen Dynasty, including Gia Long, Minh Menh, Thieu Tri and Tu Duc, there was a total of fourteen royal decrees against Catholicism. Many of these decrees were issued immediately before and after the French invasion of Vietnam during the reign of King Tu Duc. By restricting the actions of missionaries, the Nguyen Dynasty hoped to halt the invasion of the French.

In 1820, after defeating the Tay Son army, Nguyen Anh proclaimed himself King Gia Long (reigning from 1802 to 1819). He marked his victory by changing the country's name from Dai Viet (Great Viet) to Vietnam. Nguyen Anh was dependent upon the support of Catholicism, especially the actions of Bishop Pigneau de Behain—representative of the Bishops' Office in Dang Trong. Furthermore, Nguyen Anh's son, Prince Canh, had been sent to study in France at the age of six. Therefore, Catholicism under the Nguyen Dynasty was favorably spread. However, his courtiers' warnings, coupled by his own realization of the threat that missionaries posed to his rule, resulted in a change in the Nguyen Dynasty's laissez-faire policy towards Catholicism. Although the Nguyen Dynasty had never passed a royal decree against Catholicism, in a decree on holidays issued in 1804, King Gia Long stated: "The Portuguese religion is an exotic religion which has been spread secretly throughout the country. Although the court has tried to prevent its development, it still exists. Hell is a horrible place which is set up to threaten the bone-heads; heaven is a dreaming place which is used to seduce the naives. This religion has deceived a lot of fools. Hence, from now on, all activities related to Catholicism such as repairing old Catholic churches or building new ones are completely banned."

King Minh Mang had a profound knowledge of Confucianism. He advocated for the establishment of a feudal, centralized country in accordance with the Confucian ideology and the maintenance of the traditional cultural values of Vietnam. However, his policy was hindered by the spreading of Catholicism. Consequently, during his reign (1820-1840), he adopted five royal decrees against this religion in 1825, 1832, 1836, 1838 and 1839. The royal decree in 1832 stated that: "Catholicism has been present in Vietnam for a long time. Only foolish people are seduced by it. Heaven is unreal. Moreover, it is wrong not to worship deities and ancestors. What the priests preach is heresy. Therefore, I announce that those who made the mistake of following Catholicism will have a chance to escape punishment by abandoning this religion. Those who refuse to abandon Catholicism will suffer harsh punishments."

Together with decrees against Catholicism, King Minh Mang also promulgated educational policies based on the moral standards of Confucianism. One of the typical examples was the issuance of the Ten Commandments in 1834. It was written in the preface of the Ten Commandments that: "The most essential thing in ethics is to maintain a pure conscience. A man of pure conscience is a man of long-lasting good fortune. A good heart is the center of a man. A man with a good heart will always receive good luck; a man with an ill heart will always suffer from bad luck. Customs are closely related to human life. Once people practice good customs and habits, criminal laws can be abolished and warfare will not occur. The entire world will enjoy peace." Particularly, it was asserted in the Clause 7 of the Ten Commandments that Catholicism was a heresy and was against the traditional cultural values, and therefore should be abolished. King Minh Mang's teachings were first and foremost aimed at the people on the outskirts of the Imperial City of Hue, but their impact was spread throughout the country later on.

In 1838, a Vietnamese delegation was sent to France by King Minh Mang to hold talks about Catholicism. However, the delegation was forced to return to Vietnam empty-handed as the Society of Foreign Missions of Paris had asked King Louis Philipe not to meet them. This caused the following Nguyen Kings to become more agitated and impose harsher measures against Catholicism. (The Vietnamese delegation's journey lasted for two years and by the time they returned, King Minh Mang had passed away.)

The measures against Catholicism under the reign of King Minh Mang mainly aimed to prevent its development and were taken only when necessary. Therefore, the number of parishioners continued to grow. In 1800, there were 310,000 parishioners in Vietnam, but by 1840, this figure had soared to 420,000 parishioners, including 15 missionaries and 150 Vietnamese priests.

After coming to the throne, King Thieu Tri continued King Minh Mang's restrictive policies on religion. His reign lasted from 1841 to 1847, and he was at first quite tolerant toward Catholicism. However, the French missionaries abused his tolerance to promote their missionary work throughout the country and interfere with the political affairs of Vietnam, especially after the event of Da Nang. In 1847, King Thieu Tri successively issued two royal decrees against Catholicism. One of them was aimed at the officials only: "Catholicism is a heresy which deeply deludes the people. Not only have the common people been affected, but some officials have been seduced by it as well. It is time to stop its development."

Under the reign of King Thieu Tri, there were totally 25 missionaries, 4 bishops, 180 priests, 1,000 preachers, 500 postulants, 1,500 nuns and 200 evangelization points.

King Tu Duc reigned from 1848 to 1883. During this time, the political situation of Vietnam was developing complicatedly, and the evangelization of Catholicism showed many signs directly related to the political affairs of Vietnam, the peak of which was the French-Portuguese invasion of Vietnam in 1858. These circumstances ignited King Tu Duc's hostility toward Catholicism. It is also opined that his opposition to the religion was strengthened by his prejudice against missionaries, especially Bishop Pellerin, who had supported and encouraged Prince Hong Bao, his elder brother, to oppose him. Under King Tu Duc's reign, seven royal decrees against Catholicism were passed successively in 1848, 1851, 1855, 1857, 1859, 1860 and 1861. The earlier decrees in 1841 and 1853 showed the King's tolerance since he distinguished Catholic followers from missionaries and Vietnamese priests. However, in the following decrees, especially the one issued in 1856 after the French invasion of Da Nang, the King became stricter in forbidding Catholicism and less inclined to make a distinction between its followers and missionaries.

Efforts to prohibit Catholicism in Vietnam came to a halt when King Tu Duc signed two peace treaties, Nham Tuat Peace Treaty in 1862 and Giap Tuat Peace Treaty in 1874, that gave six provinces in South Vietnam to France. Part of the treaties included clauses related to the spread of Catholicism. After the signing of these treaties, a movement to "squash Western invaders (French colonialists) and resist the heresy (Catholicism)" was launched by feudal intellectuals. In 1874, the leaders of this patriotic movement petitioned the court to be allowed to organize a resistance movement against French invaders and Catholicism. Then they prepared the forces and delivered a proclamation to mobilize the people to join the movement. The movement developed mostly in the northern and central regions of Vietnam and lasted until 1888.

In spite of all attempts to prevent the development of Catholicism in Vietnam, the religion still developed dramatically until the end of King Tu Duc's reign (in the latter half of the nineteenth century) in all aspects: the number of parishioners and priests, the scope of activities, and the structure of organization. In 1880, there were totally 500,000 parishioners and 227 priests (including 380,000 parishioners and 147 priests in Dang Ngoai, and 120,000 parishioners and 80 priests in Dang Trong). Important changes were especially made to the organizational structure during this period, one of which was the establishment of eight dioceses as follows:

- In 1844, Pope Gregorius XVI divided the Diocese of Dang Trong into West Dang Trong (Sai Gon) including six provinces of South Vietnam and Cambodia to be overseen by Bishop Lefebvre and East Dang Trong (Qui Nhon) to be overseen by Bishop Cuenot (also known as The in Vietnamese).

- In 1846, Pope Gregorius XVI further divided the Diocese of West Dang Ngoai into West Dang Ngoai (Hanoi) and South Dang Ngoai (Vinh) which came under the control of Bishop Retord and Bishop Ganthier respectively.

- In 1848, Pope Pius IX further divided the Diocese of East Dang Ngoai into East Dang Ngoai (Hai Phong) under the control of Bishop Jenonimo Hermosilla (also called Liem in Vietnamese) and Central Dang Ngoai (Bui Chu) under the control of Domingo Marti (also called Gia in Vietnamese).

- In 1850, Pope Pius subdivided the Diocese of West Dang Trong into West Dang Trong under the rule of Bishop Lefebvre and Phnom Penh (Nam Vang) including Cambodia and some provinces of South Vietnam under the rule of Bishop Michel (also known as Mich in Vietnamese). Simultaneously, the Diocese of East Dang Trong was subdivided into North Dang Trong (Hue) under the rule of Bishop Pellerin and East Dang Trong under the rule of Bishop Cuenot (also known as The in Vietnamese).