A symposium was held in July on the work of the late Duong Quang Ham — an expert on Vietnamese literature who died in action in 1946 in the early stages of the First Indochina War.

It commemorated his 95th birth anniversary — he was born in 1898 — and it brought back fond memories of a teacher I greatly admired.

His erudition, dignity, and, above all, the integrity he showed under the regime of French colonialism, when he was teaching French and Vietnamese at the Protectorate College in Hanoi was an example for many of us.

I also thought of other men who, like him, had belonged to the generation of "modernist" traditional letters that witnessed the establishment of the colonial administration.

Those people were the product of absolute monarchy in Vietnam (10th-19th century) which, in the 11th century, founded the first university — the Temple of Literature in Hanoi — and instituted a full-blown system of examinations to recruit professional administrators to take over most of the important functions until then per- formed by members of the aristocracy.

Feudal education focused on morality, philosophy and belles lettres. From the 15th century greater stress was laid on the Co fucianist in junction for absolute loyalty to the monarchy.

When the country was conquered by the French by the end the 19th century, patriotic scholars rallied to the Can Vuong (Save the King) movement, the king being to them the symbol of the country

The royalist cause disintegrated at the turn of the century. Other patriotic movements were then launched by old-school scholars who had turned "modernists" — Phan Boi Chau with his anti-imperialist stand, Phan Chu Trinh who tried to win support from democratic forces in France for an anti-feudal struggle, and Ho Chi Minh who put the anti-imperial struggle in the broader context of internationalism1 and finally succeeded in ridding the country of colonialist domination through the August Revolution of 1945.

Meanwhile, many of those "modernists" who were not directly engaged in revolutionary activities were obliged to work in the colonial administration without departing from their patriotic stance One such staunch patriot was my college teacher, whose father and brother were exiled to Poulo Condor Island.

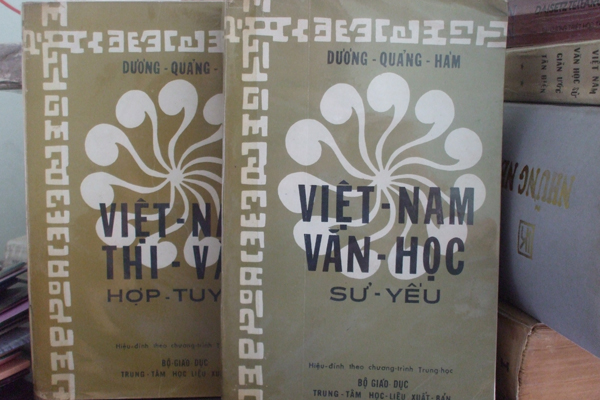

Duong Quang Ham devoted himself to the teaching of the mother tongue and vernacular literature. He put up a one-man cultural battle by writing "Fundamental History of Vietnamese Literature."

The book, published in 1943 under strict censorship, is noted for the author’s clear-sighted analysis: "Amongst our scholars and writers not a few snobs can be found who do not know how to make a correct choice to preserve their originality and keep their identity But our people are blessed with an extraordinary vitality: they did not let themselves become assimilated through the long centuries of Chinese domination. On the contrary they knew how to draw from Chinese culture to create an organised society and a literature of some stature... We therefore may hope that in the future we can find good points in French literature to make up for what is lacking.

First of all we may be able to take up Western scientific methods in studying questions relating to our culture and to the life of our people. We may make use of what is best in French literature to strengthen our national spirit and pave the way for a literature compatible with the present conjunction while keeping intact the traditional hallmark. Such is the common task of our scholars and writers."