The shape of Vietnam has given rise to many picturesque comparisons. Sometimes it is referred to as a big ’S’ on the eastern edge of the Indochinese peninsula. Sometimes it is the Pacific balcony; or again, given its strategic position in the heart of Southeast Asia, a crossroads of East-West civilizations and relations.

Sometimes it is a dragon stretching 1600km (as the crow flies) from north to south, only 50km wide at its narrowest point; its backbone is the Truong Son mountain range, location of the famous Ho Chi Minh Trail.

And yet again it is a carrying pole balancing two baskets of rice, the Red River delta in the north and the Mekong delta in the south.

The Vietnamese term dat nuoc (dat, land; nuoc. water), refers to the country, the fatherland. It evokes the two essential components of the economy and civilization of a people whose way of life is governed by the planting of rice in flooded fields.

Another term that refers to the country is non song (non, mountain; song, river): the immutable rivers and mountains that are the eternal face of the country. Hills and mountains cover three-fourths of the 330,000sq km of Vietnam.

Two popular Viet legends, based on geography, point to 1he dawn of Vietnamese history. Their action is situated in the north of the country, in the cradle of the Vietnamese nation.

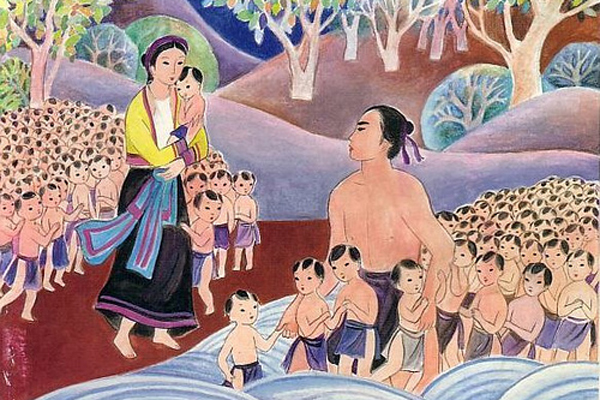

The first is a legend of the mythic ancestors of the Vietnamese people: the Dragon of the Seas and the Fairy of the Mountains. Of the hundred sons who were born to them, half went to the mountains, and half to the plains.

The eminent French geographer, Yves Lacoste, sees in this story the reflection of the formation of the Vietnamese people, whose conquest of the Red River delta came relatively late, and was only made possible after the population, which had settled first in the foothills, had grown large enough to handle the construction of dikes along the rivers and coasts.

The struggle against the devastating floods that recurred each year in the Red River basin is told in another legend, that of the eternal conflict between the Spirit of the Mountain and the Spirit of the Waters for the hand of a beautiful princess.

Vietnam's climate is hot and humid. On average, there are 200 hours of sunshine a month in summer, and 130 in winter.

To describe the torrid heat of the sun, the Vietnamese say nang chay cat - ’heat that burns your kidneys’; nang vo gioi - ’heat that bursts the heavens'; nang nhu dot (luoc, nau, nung, thieu) - 'heat that burns, boils, cooks, roasts, cremates'.

It rains an average of 100 days a year. The combination of this heat and humidity accounts for the luxuriant vegetation. Nature and life move to the rhythms of the gio mua (seasonal winds, or monsoons).

Especially in the South, two distinct seasons are clearly determined by the monsoons: the dry winter season and the rainy summer season. Even military maneuvers must take this feature into consideration: the guerrilla takes advantage of the rainy season, while pitched battles always wait for the dry.